The following was originally written by Mark Brim, AIA, LEED AP, a Design Leader at DLR Group in Omaha, and shared internally with the company.

When was the last time you picked up a pencil to draw? That question, and my own love of sketching, recently led me to read Paolo Belardi’s excellent book, Why Architects Still Draw. In it, he points out that: “Sketching is a quick, readily available, dense, self-generative, and, above all, extraordinarily communicative notational system” that’s a “precious tool for all human activities that deal with creativity.” That’s an idea that I can get behind 100%.

Since we began adopting CAD in the 80s and 90s, we designers have been using an endless series of digital tools to create, compose, and ultimately produce our deliverables. And now more than ever our emerging designers are often doing their design thinking through mice and software. But hand-drawn sketches can work so much more powerfully than other methods of communication. Sketching is human and tactile; it opens doors to ideas that you might not have come up with otherwise; and it lends itself to connection and memory.

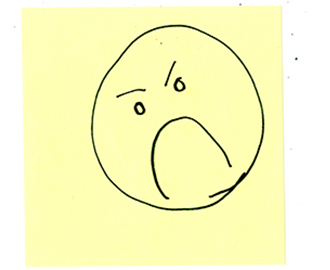

I remember a day twenty-something years ago when my daughter demonstrated the power of sketching. After washing the family Oldsmobile Custom Cruiser, and putting away the bucket and hose, I came back to the car to discover a sticky note attached to the otherwise spotless bumper: a simple sketch of an unhappy face (below), drawn by my four-year-old daughter as a performance review of dad in the wake of some unfair fatherly action I’d taken earlier. I don’t remember what I’d said or done to earn the demerit. But I’ve always remembered that sketch. In that way, it was more powerful than any tantrum she might have thrown or any frustrated words she might have said at that time. And sketching allowed my daughter to express herself clearly, more quickly, and in what’s turned out to be a lasting way (and perhaps I should clarify that this is a good memory, a cherished one).

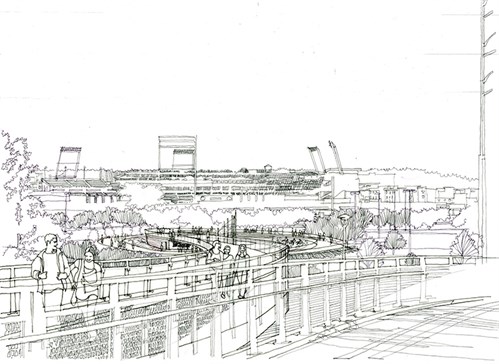

When you have an idea, it comes with an initial energy and passion. It’s dangerous to delay that thought. As time elapses the vitality of the idea fades. Wait to see that idea through and you risk losing it – especially since, for many of us, ideas arise when we’re away from our desks and schedules and habits: on a four-hour drive across the prairie; on a walk; in a café; even in a dream. Spontaneous sketching lets you get lost in the idea right away, and ride out that initial energy to its fullest. Not to sound clichéd, but I’ve had a project challenge “a-ha!” moment while on a bike ride in the middle of nowhere, and ended up sketching out the solution on a napkin from a roadside diner (above). Eventually it had to be translated into modern digital deliverables, but if I hadn’t sketched the idea in the moment, it might not have made it back to the office with me – or at least not fully.

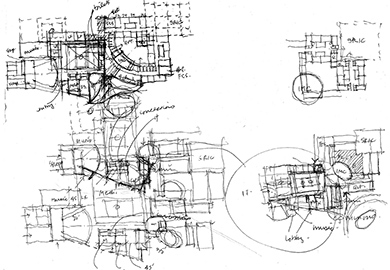

The art of sketching also informs your thinking. During conceptual phases, the act creates an interrelationship between a thought and the work. It becomes inventive drawing: a flow of pencil movement that is spontaneous and free, uninterrupted by shift-clicks and menu selections and commands. As Belardi puts it: “The creative synthesis of the sketch intimately joins the inventive act of the artist with the inventive act of the scientist, nullifying the separation between creation and discovery.”

You don’t need to be an artist or a designer. You just need an idea and a pencil. You can cultivate this skill for yourself simply by doing it. Or you could host or attend a workshop. We offered one last summer that walked participants through exercises developed by architectural illustrator Bruce Bondy. We had volunteer participation from architects, engineers, interiors designers, marketing professionals – some who were comfortable sketching, and others who were either learning or even re-learning a skill they’d let atrophy. People quickly became more focused on the ideas first, not worrying about what would have to be done on a computer.

So sketch your way through your next idea. Express what you’re thinking, and let the sketch expand your thinking. The more you sketch, the more it becomes a part of your DNA. Vincent Van Gogh points out in a letter to his brother: “the pencil is the skeleton key that springs the lock and opens the door to the dream.” With that in mind, no matter when the last time you sketched, there’s no better time than now to start.

by Mark Brim